Where Does One Thing End and the Next Begin?

An essay by Ian Monroe that explores collage as a function of edges between things.

First published 2008 in Collage: Assembling Contemporary Art, Black Dog Publishing.

A simple question at the outset, but one that rapidly becomes difficult to answer definitively without further examination. For example one would need to know which things we are referring to, a city boundary, a pair of lovers, or covalent molecules in a solution? Do my own physical boundaries extend to the work I do or to the people whose memories I have made an impression upon? Or, to take a much broader position, how do the various types of matter in the world remain differentiated, why does silver not simply merge with its cousin cadmium for example?

Of course, all of these questions have multiple and temporal solutions and depend, in part, on ontological and epistemological positions. However, it is possible to make an assertion that cuts across this group of questions as a whole. Accepting the problematic nature of language itself to be definitive, and the incessant temptation to anthropomorphise, the entire universe could be considered as a composite of the infinite number of endings and beginnings that are negotiated and renegotiated both ceaselessly and instantaneously.

If this is true, then it is possible to suggest that what constitutes the world around us is not the nature of materials themselves, but the difference between them (i.e. the exact place-in space or time-where one thing stops and another begins). With all of these minute and incremental decisions being made as matter jostles about in its Brownian fervour, it becomes clear that these interactions themselves are the foundations of being, the very nature of materiality. In other words, matter and all the structure it embodies is, at its most basic level, predicated upon the existence of the edge, a transformative instant, the moment at which an other manifests. Thus, it is not the thing in itself to which we should refer for meaning but, rather, what it is not and how it interacts with other things.

So, then, it is possible to bring this discussion to the subject of collage, which can be seen as a methodology that deploys this edge, this elemental difference between materials, objects, images and subjects as its core concern. It is this active boundary, where previously disassociated material is amalgamated, that gives collage its frisson, its efficacy as a technique. Any artist using collage, be it found film footage or magazine clippings for example, is confronted with the discrete point at which two or more previously distinct bodies collide, and here a decision is made and difference is expressed. Thus, what unifies all of these practices is not just the literal and metaphorical gluing together of things, it is the functions, the transformations performed at the edge that gain significance.

In this way, collage is analogous to the world around us but, importantly, it also allows for interactions that the world around us has not yet performed, to ask questions about difference that may never have been posited. In this essay I will explore the various edges that exist in the material world around us, and a few artists and institutions that have used collage in its expanded sense to arrive at new ways of addressing the nature of difference and being.

Chimera of Arezzo, Etruscan Bronze, 400 B.C.

CHIMERA’S EDGE — The edge defiled and corrupted, so deeply commingled, as to cause horror or revulsion

It is telling that the Greeks had an intermingled, and duplicitous mythological monster in their Pantheon, which represented a deep fear of the unknown. The Chimera was a single creature made up of multiple animals, it had the head of a lion, the body of a goat and the tail of serpent and was eventually slayed by Bellerophon*1. Chimera’s first literary appearance is in Homers Iliad as “a thing of immortal make, not human, lion-fronted and snake behind, a goat in the middle, and snorting out the breath of the terrible flame of fire” and is linked with the volcano in Lycia, Anatolia, that bears its name*2. Ovid and Virgil both mention the Chimera and, in Platos Republic, he speaks of “Khimaira or Skylla or Kerberos, and the numerous other examples that are told of the many forms grown together into one”*3. Although the exact meaning of the Chimera and its various manifestations probably was (and still is) a matter of debate, these collaged creatures were almost universally regarded as portents of pestilence and disaster. They sank ships, ruined crops, and were generally very unpleasant creatures which should be killed at the nearest opportunity.

The Chimera is, of course, a myth. But as such, it symbolises our fear regarding difference. In other words, the Greeks are worried about a possible breach in the ‘normal’ rules of differentiation, in an unauthorised mixing of categories. What is striking is that the individual, unadulterated animals do not elicit the same response. In fact, goats, lions and even serpents are variously regarded as symbols of fertility, bravery and cunning. It is only when they are merged into the single body that the creature takes on a truly horrific character. Here, it is not the content that is the source of anxiety, but the idea of an irrevocably mixed identity, of boundaries or edges that have been obscured or destroyed. What such anxiety would appear to imply more generally is that the preservation of difference has an important mollifying effect on the human perception of objects and concepts.

In David Cronenberg's 1986 horror film The Fly, Jeff Goldblum's character transforms into a human-fly hybrid as the result of an accident with his teleportation machine.

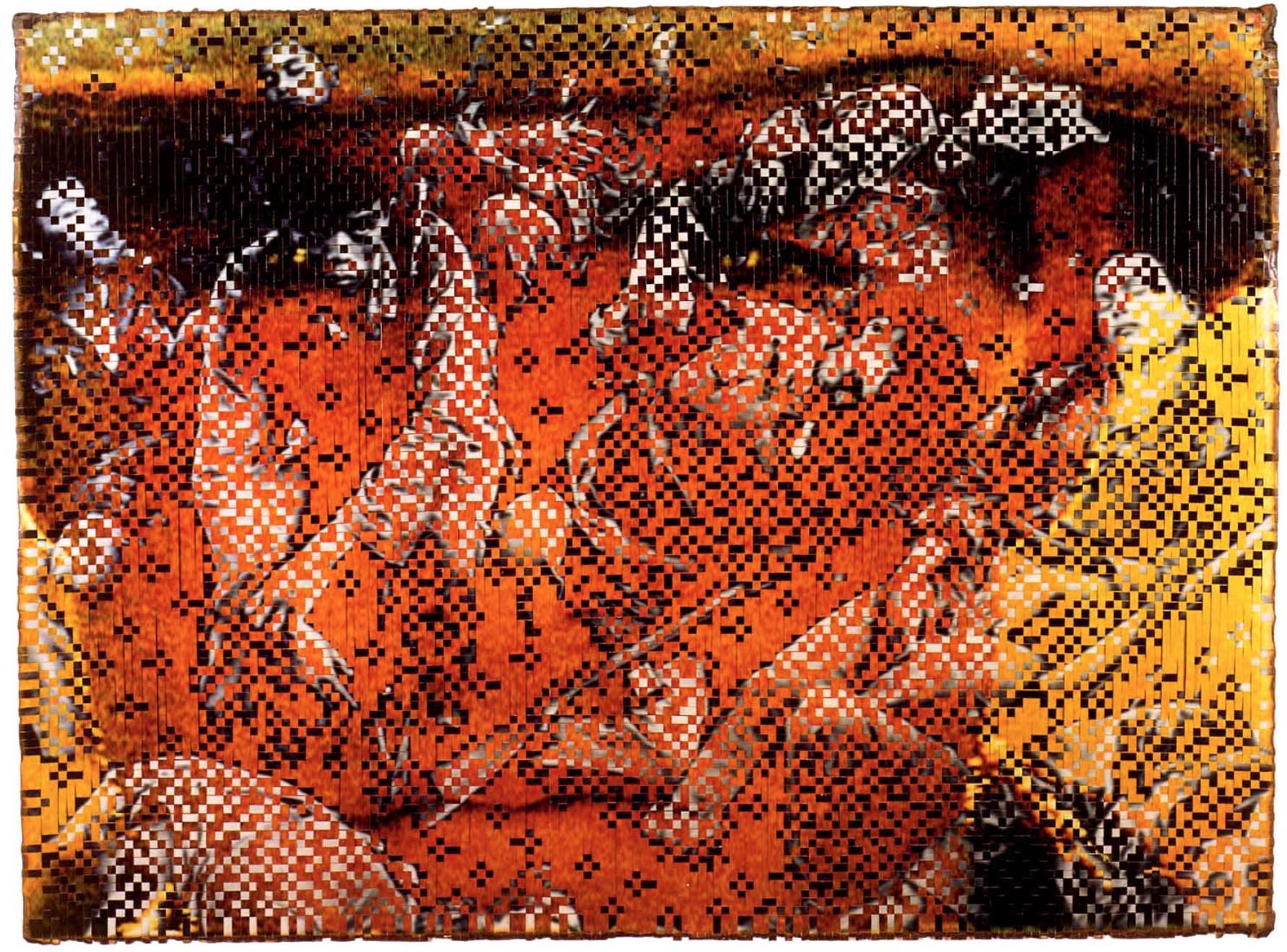

The fears concerning merged identities are explored by the Vietnamese artist, Dinh Q Le, in his hybrid images combining the ‘real’ Vietnamese homeland with those romanticised clichés proffered by American popular culture and film. Le uses a collage technique called ‘cubomania’ in which separate images are sliced into strips and woven together. In so doing, the artist affects a metaphor that speaks of the irrevocably intertwined nature-both culturally and conceptually of these two Vietnams. Curiously, this technique contains an inbuilt simultaneity, it is possible to both decode or separate the distinct original images and, at the same time, appreciate the overarching new image. In other words, like the Chimera, the edges here are both unmistakably visible yet also constitute a single, deeply blended body.

Dinh Q Le, The Persistence of Memory, 2007, 120cm x 160 cm , colour photograph, linen tape

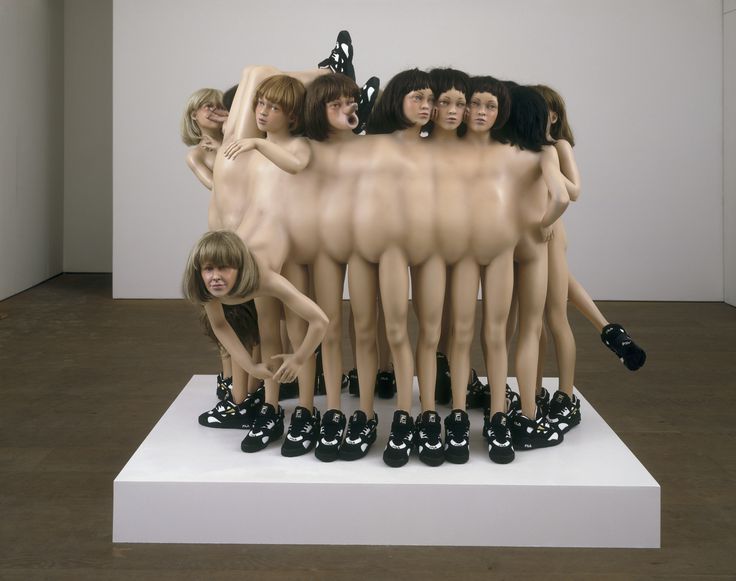

Perhaps the artistic exploration of the Chimeric Edge reached its literal apogee in the work of ]ake and Dinos Chapman in the mid-1990's. In Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic De-subliminated Libidinal Model (enlarged x I,000), 1995, the Chapmans explore the blended body in objects that repulse and attract with equal measure. In this piece—like the Chimera—we find it is the corrupted boundary that causes anxiety, not the subject matter itself. The young girls themselves, are not terrifying. Yet when 25 of them merged into one monstrous Chimera of penis-nosed urchins the work takes a far more sinister turn.

Jake and Dinos Chapman, Zygotic Acceleration, Biogenetic De-subliminated Libidinal Model (enlarged x I,000), 1995

Interestingly, the term Chimera is in use today in genetics and virology to describe a single, viable organism containing multiple genetic strains that originate from more than one zygote. This condition can occur naturally when fraternal twins merge early in gestation, or it can be induced in a laboratory environment with all the suitably disturbing results you can imagine (witness the ‘geep', a half-goat-half-sheep creation, for example, or the Zedonk, Zedkey, Dongbra, all names for the real offspring of a Donkey and a Zeebra)*4. A—still more macabre—creature is the frakensteinesque human-rabbit hybrid recently developed for stem-cell research. In a confirmation of our inherent horror at these spectres, it was not allowed to develop past an embryonic stages*5. All of these various Chimeras demonstrate our acceptance of the individual components of the creature as benign, while simultaneously feeling revulsion towards the whole. It is a matter again of edges, of our collective desire for things to remain distinct and different, to maintain a perceived order in the system of things. This is perhaps the same impulse that provokes admiration of the periodic table, for example, as elegant and efficient, with everything in its right place.

Collage then, like the Greek myth before it, allows the possibility of a contrary exploration, of confusion or intermingling of these previously distinct elements, not necessarily to shock, but certainly to speculate on the nature of difference. In so doing,a it forces us to reassign boundaries and shift our assumptions concerning the nature of being and our relationship to the external world.

Linder, Untitled,1978, photomontage, 18 x 23.5 cm

THE ERGONOMIC EDGE — The collision of humankind and matter

The collision between the natural and the unnatural and the difference between the body and the tool, is managed and mediated by the design process of ergonomics. In ergonomics, the edge is deployed to comfort and reassure, to suggest that the interface between human and machine can be productive and placid, a utopian release from hard toil. It is at this edge that the intention of modern manufacturing to melt seamlessly into the human body is expressed. Obviously, this has already happened to varying degrees in product design and, with more efficacy, in modern medicine (with implants and prosthetics), but it is clear that not everyone agrees that these are improvements.

The ergonomic edge is deftly employed in the collages of Linder, who conflates female and male porn and pin-up images with cut-out appliances, cameras and domestic objects. However, these are not necessarily the blissful harmonies between man and machine proposed by the likes of Buckminster Fuller. Instead, Linder affronts the normally comfortable ergonomic edge, and seeks to make the relationship one in which bodies appear to be either consumed by the products in question or lost in sexual frenzy with their new technological selves. Heads become irons or televisions, arms turn into vacuum cleaners, and nipples morph into the disembodied grinning mouths of models (as in Untitled, l 977). These (largely female) bodies are made to conform to a set of criteria dictated by an object, and not the other way around. Linder deploys a casualness that invests the products and objects with an almost menacing disregard for the bodies on which they have been laced and this, in turn, belies an ergonomic edge gone awry.

While Linder is an artist who provides a critique of this managed and mediated edge, there are artists who indulge in a techno-fetishism at the intersection of the body and the ethnological object. Although the ergonomic edge is mundane in its utility (associated as it is with the personal encounters each of us have with the edges of things), the prosthetic edge has been extended to the heights of fetish and psychoanalytic hyperbole in the works of artist Matthew Barney, or Stelarc, for example. Both of these artists explore a type of collaged body, but it is largely unclear where the critical value (if any) of these explorations lies. It seems more likely that these practices envelope an affirmation of and desire for the altered and expanded body, using the transgression of the body’s edge as a tool of therapeutic self-analysis. Whatever the case, these practices serve to demonstrate how a concern with the blurring of internal and external, male and female, straight or gay, and biological or technological, edges remains powerfully embedded in the human psyche.

Matthew Barney, Cremaster 3, 2002

Matthew Barney, Cremaster 3, 2002

THE INFINITY POOL — The edge of illusion and collusion

Of course, not all edges occur at the discreet point where the previously distinct body and object actually collide, much less exist. Some edges are more insidious in the way they operate, again using some measure of gestalt, but also a generous dose of fantasy and spectacle. The finite ending of one zone and the beginning of the next is a result of the perspective, both real and imagined, of the viewer. The infinity pool is delineated by just such an edge; both tantalisingly real yet ungraspable.

An example of an infinity pool, note the real horizon is fully visible beyond the illusionistic edge of the pool.

Here the edge becomes an explicit object of entertainment and spectacle, to be flirted with as a convention of belief. The pivotal agreement (or manipulation) that allows this masquerade to function is a matter of perspective; the location of a unifying eye is the users eyes, it is this that simultaneously creates and perceives the illusion.

In some ways, the photographs of Thomas Demand apply these same techniques of illusion, but crucially, the artist wants us to decipher such illusion. Demand builds extremely elaborate paper constructions of architectural interiors or locations and then photographs the model, which is subsequently destroyed. This is not to suggest that Demand is exploring the notion of infinity, or that the practice is essentially one of spectacle for, certainly, the odd combination of the mundane and the uncanny in Demands images lead elsewhere. Rather it is the underlying use of a pre-determined viewpoint (the camera) to unify and visually smooth out the construction, which also prevents us seeing the constructions proper. This denial is familiar from film sets, and so too is the operating principle, both artist and viewer know the set ends just off camera. Yet Demand does not attempt a total deceit. As Marcella Beccaria notes,characteristic of his methodology, in all cases the photograph is balanced between apparent perfection and small imperfections that intentionally signal the encounter with a mediated reality*6. Demands edges provide us with an entry point with which to pry apart the illusion, a literal and metaphoric edge to lever against.

Thomas Demand, Simulator, C-print / Diasec, 300 cm x 429 cm

CAMOUFLAGE — The Edge Erased

If Demand uses the edge to signal the presence of an illusion, then there are also illusions that attempt to obfuscate the edge, to erase its existence altogether. All forms of camouflage-whether those evolved in animals to avoid predators, or modern military systems of disguise and stealth-rely on the disappearance of edges. To complicate matters further, predators are also engaged in a process of subterfuge, they too generate their own means of blending into the background, and thus the camouflage edge continually evolves in an attempt to erase itself.

Pacific Spotted Scorpion Fish

In a sense, then, camouflage is a response to the notion of difference in its most literal form. In other words, if the body or the content of an object has no bearing on its success as a tool of disappearance, then it is free to concentrate only on the exact moment at which it collides with the world outside. This simply re-affirms that the performance of difference and differentiation is situated at the edges, not the interior, of an object.

Cryptic Leaf Frog

An example of such disparities can be found in Tim Noble and Sue Webster’s Self-Imposed Misery, 2010. This work, among other trash sculptures they have made, is situated exactly at the intersection between such a camouflaged edge and its content. Here, light is projected onto the sculpture, thus resolving its edges by creating a profile of the artists in shadow. Noble and Webster do not try to conceal the vehicle that delivers this collision, and one is tempted to unplug the light, to momentarily return the trash heap to an illegible mess. When the light is on, however, you see the amorphous collection of trash and the image it produces in the same glance. You can walk around the arrangement trying to unravel its workings, you can trace the specific pieces of detritus that define the bridge of the nose or shapes the hair. Again, simultaneity of perception plays its part as the mind considers the disparity between the literal content of the sculpture (in this case six months worth of trash) and the subject of the illusion.

Tim Noble and Sue Webster, Self Imposed Misery, 2010

These works are a kind of feedback loop of content versus edge. Each is bound to the other, locked in a struggle between the internal nature of a thing and its transformation into something entirely different, exactly at the periphery.

John Stezaker, Mask LII, 2007

THE CORROSIVE EDGE — The temporal collapse into sameness

I have referred to the active edge, a zone where a very definite process or transformation occurs. While, in many cases, this process is additive in nature, it can also be one of attrition, of the gradual loss of separateness. Corrosion at an edge occurs with the interaction and degradation of originally distinct materials, either through the exchange of content or the flow of energy (oxidation and electrolysis in the natural world) over a period of time. It is this temporal dimension that marks out the difference of the corrosive edge to that of the Chimeric edge for example. In this system nothing is stable and, as time passes, the inability to distinguish a materials previously individual properties becomes inevitable.

John Stezaker’s Masks series exploits this confusion and combines it with an, almost accidental, economy of means in the Way edges interact. In this series Stezaker has placed unaltered postcards of various landscape scenes over images of faces. Crucially, Stezaker has not cut into or manipulated the edges of the postcards and, as a result, a jarring difference between the two images becomes manifest. In these Works, the individual features of the landscape resolve into the facial characteristics; a rock forms an ear, a cave mimics the curving gape ova mouth, a stalactite drops like a nose. The edge that served so well to separate the original images now gives way to one that becomes caustic in the conflation of face and landscape, image and form.

Such a relationship also plays itself out in the video work of the artist, Sheena Macrae. Macrae makes Works comprised by composited television and film footage where layering, slicing and editing conspire to reduce the primacy of the original material. In Dallas, 2005, Macrae combined 18 episodes from the television series of the same name into a 50 minute moving palimpsest of the original. In a similar vein, but using a technique closer to cubomania, her Odyssey slices up Kubricks 2001 : A Space Odyssey, redelivering the film in seven minutes through a composite 20 layers. In both Stezaker’s and Macrae’s work the edge becomes corrosive through the interaction of the component layers. In a sense, this is the general tendency of collage, to mix and merge elements, and to erode their individuality

Rust on a ship hull. This process involving iron is called oxidation, when it's wood, we call it fire. Either way, oxygen is corroding the base material.

Andrew Moore, Revel, image courtesy the New Yorker.

THE MUNICIPAL EDGE — The collage edge writ large, made manifest in concrete and steel

We encounter edges on scales that are often beyond the scope of individual agendas, or even gazes. They instead reflect larger collective desires, such as political boundaries, or the way a city becomes a type of fractal collage of colliding uses, zones, economics, and building practices. One could argue that the organising principle behind society as a whole is the management of boundaries, the control of territory, with varying effects at local levels. As Anton Picon says in his essay “Anxious Landscapes”, “in following the lines and folds of the social body like both a tight-fitting and creased garment, tight and creased to the point of rupture, technology and the city seems to organise themselves around thresholds and edges too numerous to count”*7. Here the manipulated edge is extended to the grand scale of earthworks of both artistic and municipal origin.

One of the most striking modern examples of a manipulated edge —a Wild edge made innocuous— is the, now completely paved, Los Angeles River. Previously the River used to breach its banks seasonally, cutting a meandering and devastating path through the burgeoning city. Now, it has succumbed to a paranoid fear of the unbounded edge, an edge previously beyond the efficacy of commerce and domesticity. It has become an emblem of an alienating and post human industrialised landscape, little more than a seam cut through the city. If the taming of this unruly phenomenon exists (for the time being) as a marker for civic triumph (and possibly as a battle won against the formless), it also stands as a hubristic symbol of our collective desire to suppress the entropic, the boundary that must be held to its terms if we are to get on With our lives.

Hence, this once uncontrolled seasonal riverbed has been transformed into a 51 mile long concretised viaduct that bears little resemblance to its previous form or path. This commanding impulse over boundary is never satiated and, in fact, becomes an iterative self-consuming project. To quote Picon again: “the city stops being in the landscape, as a sort of monumental signature, to become, progressively, in and of itself, landscape. ln less than a century, we go from the enclosed city profiled against the horizon of a fairly cultivated countryside, to the spectacle of the big city from which our eyes can no longer escape”*8.

This edge is voracious, consuming all who gaze at it. The municipal edge operates on scales that dwarf our previous concerns for corporeal boundaries. Instead, it gathers us up en masse and shoves us on subway trains and stacks us up in skyscrapers. This notion of the individual consumed by the city has a long history in popular film (the Los Angeles River, in particular, has featured frequency in many post-human and apocalyptic scenarios). Most-generally American filmic attempts to demonstrate how humanity has been subsumed by its cities end up celebrating the heroic possibilities bound up in such non-places. This is the paradox of the municipal edge, it has no room for us, yet we are drawn to it because it is ours. This edge is collage on its grandest scale, our collective societal collage, which has moved over our horizon, eclipsing even itself.

Thus collage turns us out from art practice, and it becomes a tool to critique or engage with modern cultural conditions and beliefs. Collage continues to be reinvested by artists as is evidenced by the widely varying artists collected in Collage: Assembling Contemporary Art. In part, this is because collage runs counter to our desire to categorise, to separate, and sequester the things around us. It is also because collage resists the prescriptive limits of discrete bodies, giving way to the novelty, or even dread, of the hybrid or the spectral, the physical proximity of objects and images pre-empts a cognitive meshing of the subjects and boundaries. It is these agencies of collage and, more specifically, its edges which can be brought to bear on the World around us. What is unique to collage, then, is that the artist-and, in turn, their audience-are confronted with the phenomenology of difference or, more simply, the endings and beginnings of things.

Graves, Robert, The Greek Myths, London: Penguin, pp, 252-256.

Homer, Iliad, London: Penguin, 1998, pp. 179-182.

Plato, Republic, Indianapolis: Hackett; Publishing Company, 2004.

“Its a Geep", Time Magazine, 27 February 1984.

Mott, Maryann, Animal-Human Hybrids Spark Controversy, National Geographic

News, 25 January 2005.

Beccaria, Marcella, Thomas Demand: The Image and its Double Skin, 2002, p. 17.

Picon, Anton, “Anxious Landscapes”, Grey Room, No. 1, p. 73.

Picon, “Anxious Landscapes”, p, 67.